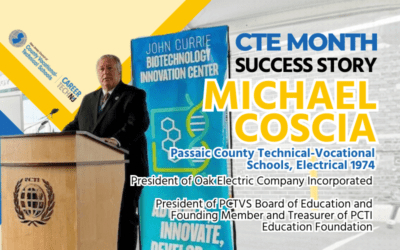

Students enrolled in an apprenticeship program at Ocean County Vocational-Technical School.

Read this article as it originally appeared in New Jersey Business Magazine.

By Meg Fry

Providing great opportunities for workers and employers, apprenticeship programs also face

COVID-19 challenges.

After two years of support from Gov. Phil Murphy’s administration and tens of millions of dollars in funding, paid apprenticeships in New Jersey have increased by 64%, with more than 1,000 registered apprenticeship programs educating and employing more than 8,500 apprentices at the start of this year.

“The investment the state has made in apprenticeships in recent years is unprecedented,” says Nicholas Toth, assistant director of the New Jersey Department of Labor Office of Apprenticeship.

The appetite is there in terms of government, academia and industry working together to achieve increased economic opportunity, adds Nicole Sandelier, director of economic policy research at the New Jersey Business & Industry Association (NJBIA). “The biggest struggle was changing the social stigma and pushing out the message to employers that this could be great for the right student,” she says.

However, when the COVID-19 health crisis hit, everything changed.

Related technical instruction and some on-the-job training has been postponed or limited, further affecting the pipeline of skilled workers in critical sectors, while future sources of funding have been threatened by a shuttered economy.

Still, now is no time to retreat, says Aaron Fichtner, president of the New Jersey Council of County Colleges and former New Jersey State Labor Commissioner under Governor Chris Christie.

“Our employers are trying to get a handle on what this economic recovery will look like, and if their needs will change from a skills standpoint,” he says. “But there is also incredible reason for all of us to pull together and find new models of educating and training people in a much more efficient manner.”

“Apprentices earn while they learn and get to start their careers a few years before they graduate from college.” — Nicole Sandelier

Growth and Benefits

Prior to COVID-19, registered apprenticeships in New Jersey were growing steadily.

Designed to move high school graduates, college students, and entry-level employees into more highly-skilled occupations, employer-run registered apprenticeships combine at least 144 hours of related technical instruction (RTI) at four-year colleges, community colleges, vocational-technical schools, and apprenticeship training schools with at least 2,000 hours annually of paid, on-the-job training (OJT).

Employers gain increased productivity and safety in the workplace while reducing turnover rates and the costs of recruitment, while employees gain pathways to lucrative careers and sometimes even higher education.

“Apprentices earn while they learn and get to start their careers a few years before they graduate from college,” Sandelier says. “Then, because they are put on a clear path forward, they become economically more likely to buy a home or start families earlier.”

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the average starting salary of a registered apprenticeship graduate is more than $50,000, while the average New Jersey college student graduates with more than $30,000 in debt, Sandelier adds.

Employers typically subsidize some or all of the costs of RTI for their apprentices, with some even creating pathways for employees to earn college degrees in addition to nationally recognized industry credentials, says Judy Savage, executive director of the New Jersey Council of County Vocational- Technical Schools.

“For example, [architectural and construction woodwork] apprentices at Eastern Millwork in Jersey City receive paid OJT, training at the Holz Technik Academy in additional technical skills, further education at Hudson County Community College, and the opportunity to earn a paid-for, four-year degree,” she says.

Such programs are popular and highly competitive, Savage adds.

However, not everyone is cut out to be an apprentice, says Patricia Moran, director of

apprenticeship at the New Jersey Manufacturing Extension Program. “Our pass rate is about 32%,” she says.

Furthermore, it is challenging to find employers willing to make long-term commitments in their employees, Fichtner says. “But there is growing understanding and momentum that this is a model we really need to embrace here in New Jersey,” he adds.

Increased state funding, such as the Growing Apprenticeship in Nontraditional Sectors (GAINS) grant, certainly has helped, Toth says.

“We understand that when an untrained employee is hired, they may not be productive on Day One, so we try to help companies with the seed costs up front to train them,” he adds.

The GAINS grant provides up to $8,000 in wage reimbursement for the first six months of employment of newly hired apprentices and offsets costs for training apprentices.

“We also were going to be a big innovator relative to what other states were doing with our NJ Pathways Leading Apprentices to a College Education (NJ PLACE) 2.0 program,” Toth says, touting an update announced in January by Governor Murphy to provide financial assistance for students participating in a registered apprenticeship program while also enrolled in a college degree program.

“The idea here was to alleviate much of the economic burden that a student has going through college,” Toth says. “If we could get people paid work that also was credit bearing, that was a model we wanted to promote.”

Then COVID-19 hit, Toth continues, and some apprenticeship and training programs have been postponed or limited due to the health and economic crisis, he says.

“The hallmark of apprenticeship programs is hands-on education,” Fichtner says. “But it’s hard to learn how to weld or work a computer numerical control (CNC) machine by watching it done online.”

Still, many have attempted to provide virtual RTI while continuing with limited, socially distanced OJT.

Savage said vocational-technical schools across the state have joined thousands of educators in going virtual. “Instructors had to quickly get comfortable with new technologies to continue remotely,” she says.

It was like the transition toward technology and artificial intelligence expected 10 years from now was suddenly happening within two weeks, Sandelier says, with that in itself potentially providing more opportunity. “Now that everything is done online, is that technology here to stay?” she asks. “If so, there are certainly more opportunities for apprenticeship programs in the tech space.”

An increased focus on emerging industries outside of skilled and building trades, such as construction, manufacturing, electrical and plumbing, and heating, ventilation and air conditioning, already had been a priority of Governor Murphy’s administration, with new apprenticeships increasing prior to COVID-19 in the fields of information technology, cybersecurity, energy, hospitality, transportation and more.

In addition to addressing the current health crisis, paid apprenticeships can also help to address inequities in the workplace, Toth says, with 63% of apprentices funded through GAINS grantees identifying as Latino, Black, and/or female.

“We were doing about twice the state average in placements of Black, Latino and women apprentices in state programs,” Toth says. “We also want to continue to divert our resources to the folks who need it most, because at the end of the day, the socioeconomic category is the most important, with people often having a hard time getting the funds, childcare and transportation needed to invest in themselves and their careers.”

Postponed programs such as the Pre-Apprenticeship in Career Education Program (PACE), which trains potential apprentices in entry level job skills and competencies, open career possibilities to everyone, he adds.

“We provide someone, maybe a reentering citizen, maybe a high school dropout, with basic occupational education while providing them access to different work environments,” Toth says.

“That individual then lands in an apprenticeship program and on a career path.”

Employers and industry associations, including NJMEP, are following suit in the wake of COVID-19.

“With our new program, Project 160, we’re focusing on the unemployed or underemployed in Camden, Newark, Trenton and Paterson,” Moran says.

“We’re training 40 people from each of those hubs in safety, quality, production and process, and maintenance credentials and trying to get them placed in permanent manufacturing positions while continuing their studies. Then if they’re a good employee, the employer can put them into an advanced placement apprenticeship program,” Moran says.

Pandemic Challenges

While there certainly have been positive outcomes for apprenticeships after COVID-19, many challenges facing both employers and employees currently remain unaddressed.

“For example, employers concerned about bringing their own employees back into the workspace will likely be reluctant to bring in students for work-based learning,” Savage says. “Though, employers also need to consider whether the pandemic may accelerate some retirements.”

Furthermore, will the level of funding remain consistent for apprenticeship programs as the state recovers from the initial COVID-19 pandemic?

“We’re still figuring out what the short-, medium- and long-term plan is for this,” Toth says. “Our tax revenues are down and the funding for most of our apprenticeship programs is through a revolving account funded through income tax receipts.”

On a positive note, NJDOL was recently awarded a $450,000 grant by the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) to expand apprenticeship programs. NJDOL will use these funds to register additional apprenticeship programs in the healthcare field in response to the needs created by Covid-19. The funds will help increase participation of underrepresented populations, namely women and minority groups, by enhancing technology and data-sharing across the state to better serve current and future apprentices.

“New Jersey will continue to build on its commitment to support apprenticeships that lead to sustainable wages for women and people of color in the healthcare sector” says Labor Commissioner Robert Asaro-Angelo, in response to the grant.

Toth believes there will continue to be a clear role for apprenticeships as New Jersey rebounds.

“With a huge turning of the labor market, people will not only be looking for jobs, but also may be looking to switch careers,” he says.

Fichtner says apprenticeship is just one way forward toward becoming a more inclusive and resilient state, particularly in what is now a rapidly changing economy.

“It is still important that we find new models of education aligned with the needs of employers, with employers as true partners,” he says.

64% Increase in paid apprenticeships in NJ

After two years of support from Gov. Phil Murphy’s administration and tens of millions of dollars in funding, paid apprenticeships in New Jersey have increased by 64%, with more than 1,000 registered apprenticeship programs educating and employing more than 8,500 apprentices at the start of this year.

Requiring Apprenticeships Limits Opportunity

Chrissy Buteas, chief government affairs officer for the New Jersey Business & Industry Association (NJBIA), says that when Gov. Phil Murphy signed a law last year that registered apprenticeship programs be required for any company bidding on public projects, he prohibited small businesses from being able to do work they traditionally had – an issue made more glaring as small businesses try to rebound from the COVID-19 crisis.

“For instance, if you are in the flagpole installation business, and you need to install on a municipal building, you need to enroll in a registered apprenticeship program, which is not as easy as it sounds,” she says.

“For businesses that are too small to start their own program, they are charged thousands of dollars to partner with an association that offers one,” she says. “It’s a limiting factor … something well intended that has gone too far.”

Exothermic Excels at Workforce Development

Manufacturer helps ex-convict receive the training he needs to succeed.

Exothermic Molding, a boutique contract manufacturer founded in 1971 that serves the lab and medical device industries, has been hiring and training the formerly incarcerated to work at its 10,500-square-foot Kenilworth facility for a number of years because “it’s the right thing to do,” says President Paul Steck.

Among them is Jalil Fenney who, at the end of last year, completed training under the New Jersey Manufacturing Extension Program’s (NJMEP) Pro-Action Education Network. The network offers scalable platforms that, among other things: prepare students and workers to fill open positions at manufacturing firms; refresh the skills of incumbent workers; and facilitate collaboration between education and workforce development stakeholders.

Fenney went through the 18-month course that, upon completion, enabled him to become a certified production technician at Exothermic. He enhanced his skills in using measuring tools such as micrometers and vernier calipers, as well as learned about lean manufacturing and six sigma processes.

“Jalil knows that time relates to cost in the manufacturing setting, and what he has learned in the course will help us achieve our goals,” Steck says, adding that he has seen efficiencies and cost savings in operation thanks to Fenney’s training.

Exothermic Molding is believed to be the oldest reaction injection molding (RIM) business in the country, but Steck says, “You might say that we are molding people, not just plastic. As a direct result of this training program, we now have a highly motivated employee who we are able to retain and even promote from within. This will pave the way for others in the company to see a future of growth for themselves, as well.”

Exothermic has recruited former convicts through the assistance of the Urban League of Union County.